Le Tour de France: Stage 5 – Les Sables d’Olonne-Bayonne, 1922

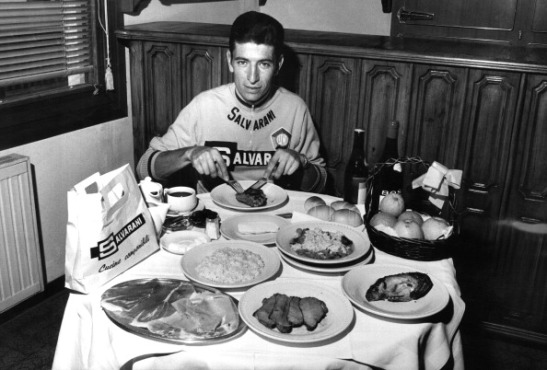

Robert Jacquinot taking a break to eat at a cafe in Hostens during stage 5, Les Sables d’Olonne – Bayonne, 3 July 1922

It is perhaps my favourite cycling related photograph, a framed reprint of which sits on my bookshelves. It was taken during Le Tour on 3 July, 1922, in the commune of Hostens somewhat over two-thirds of the way into the 482 kilometres of the 5th stage from Les Sables d’Olonne to Bayonne. Robert Jacquinot, the rider captured tucking into a bowl of soup, a baguette, and a glass of wine, had lost the yellow jersey on the previous stage after suffering several punctures and losing 1 hour 41 minutes to Eugène Christophe. When the photo was taken he had ridden around 340 kilometres that day on top of the 1569 kilometres reeled off in the previous four stages. Notwithstanding that there was a rest day in between each stage the delicacy with which he appears to be eating his soup belies the physical effort involved before he reached the café.

The photograph also speaks volumes of the differences between the early years of Le Tour and today. Jacquinot’s workaday steel-framed bicycle is a far cry from our modern multi-geared lightweight carbon superbikes. The driving goggles and his mud spattered legs attest to the conditions of the roads, as do the spare tyres wrapped around his shoulders in case of puncture; there was no handily placed team-car or neutral support motorbike for the riders of the 1922 Tour from which to grab a spare wheel or a replacement bike. It also tells us about a very different approach to watering and fuelling than the science based and carefully planned diets of modern elite athletes.

In 1903 Le Tour took no responsibility at all for feeding the riders who were expected to make their own arrangements, though the first 50 finishers could expect a per diem payment of 5 francs to cover expenses. Before, during, and after each stage the riders would have to source their own food. Breakfasts, lunches and dinners at hotels, cafés, and tabacs. Baguettes, milk, and butter from boulangeries or local farms. And, occasionally they resorted to theft, as with Marcel Kerff during the penultimate stage between Bordeaux and Nantes when he stole a loaf of bread and shared it with other riders, including the German Josef Fischer, winner of the inaugural Paris-Roubaix in 1896.

The food they ate was simple, or, to be more precise it was what was available. General advice on a healthy diet advocated red meats, bread, eggs, milk, vegetables and fruit, while contemporary ideas on nutrition for athletes tended toward a focus on a high-protein, high fat diet with lots of meat. In 1897 the famous Welsh track rider, Jimmy Michael, spoke of his diet in an interview. Chops, beef, bread and tea for breakfast with an occasional egg. A lunch of meat, mostly beef, no vegetables, washed down with Bass’s ale. More meat for supper, and either some more Bass or an egg and sherry if a stimulant was needed. Eugène Christophe ate foods to give him energy, balls of rice, ham sandwiches, bananas and chocolate. Food was bought en route by the riders who bolted down anything they could get their hands on, chickens, toast, fruit tarts, biscuits, all would be consumed with gusto. Trade sponsors and supporters supplied food to the riders seeking to ensure their men succeeded.

The need for hydration, today seen as crucial for performance, wasn’t seen as important. In fact popular attitudes maintained that too much water was positively bad. Riders did however enjoy alcohol, sometimes to their detriment. In 1903 Hippolyte Aucouturier suffered a sudden loss of form after he developed stomach cramps. He blamed it on some lemonade he’d taken from a spectator, though many others suspected it may have been the red wine he’d been knocking back throughout the day. In 1914 François Faber attacked on stage 13 from Belfort to Longwy. In the final hour he was visibly struggling, “zigzagging somewhat” according to Desgrange. With some 10 kilometres left to race he collided with a car. When he finally reached the finish line six minutes ahead of his pursuers the onlookers were “stunned by the level of his drunkenness.” And it was not just wine they drank. In 1914 L’Auto carried an advert for Koto, a wine that the ad claimed was drank by many of the riders. The secret ingredient was the finest Peruvian coca, giving it a nice, if questionable, alkaloid boost.

At a time when water supplies were not always of the highest quality alcohol could be a boon. The brewing process helped sterilise the water used in making beer, which in its finished form was at least 90 per cent water. Taken moderately it provided hydration and a small energy boost without any major side effects. In one instance beer allowed a rider to win a stage of Le Tour when, on stage 17 in 1935, Julien Moineau chose not to succumb to the siren allure of a booze-laden table offered by spectators. As the peloton stopped to enjoy the impromptu refreshment Moineau rode off and on to the stage victory leading the bunch by 15 minutes and 33 seconds at the finish line. Moineau had organized his own water stops throughout Le Tour, allowing him to maintain a breakaway if he could engineer one. It raises the intriguing possibility, never admitted by Moineau, that he had also organized the beer stop to tempt his rivals into stopping.

Alcohol could also be deadly. In 1967 Tom Simpson collapsed on Mont Ventoux. Already suffering from a stomach upset he had drunk brandy and taken amphetamines. With temperatures hitting 45º centigrade the cocktail of drugs, alcohol, and illness proved lethal. One kilometre from the summit he fell. Insisting he should ride on he was helped back on his bike, riding on for another 500 metres before he passed into unconsciousness on the bike, his hands locked onto the handlebars. Transported to hospital by helicopter he was pronounced dead at 5:40 pm on 13 July, 1967.

In 1919 post-war conditions forced the hand of the organizers of Le Tour over food arrangements. With rationing still in place Desgrange and his lieutenants decided to provide food and water stations for the first time. Riders still had to buy food if they needed to eat between the two official feed-stations on each stage but Le Tour reimbursed their expenses, as long as receipts were provided. 1919 marked, if not a softening in Desgrange’s attitude (he was ever the dictator, a patrician martinet that always knew best) then an acceptance that providing more direct support to the riders would result in better racing.

If the responsibility of Le Tour to provide nutrition to the riders was established, little else changed. As late as the 1960’s Jacques Anquetil, Le Tour’s first five-time winner, was still advocating that, “dry is best.” One of his favourite dishes was steak tartare and he was renowned for drinking lots of champagne. At the Tour du Var in 1963 he was spotted eating a huge breakfast washed down by white wine. At the same time researchers were beginning to make advances in the nascent field of sports nutrition, developing a better understanding of human physiology and how the body stores and makes use of glycogen. Gatorade, the world’s first scientifically formulated sports beverage was introduced at the University of Florida in 1965.

Cycling is an inherently conservative sport and it took time for developments to filter into a world where the soigneurs largely controlled the diets and training of their charges. Often ex-riders themselves the soigneurs held to the tried and trusted methods of their generation of cyclists. As late as the 1990’s Jonathan Vaughters was being handed bags of croissants with jelly on the bike, while mounds of pasta constituted the bulk of a rider’s diet. Now professional teams employ nutritionists and sports scientists who manage the riders diets to maximise their performance. Riders sweat is analysed to determine what customized drinks they should be imbibing. Team chefs provide a balanced and varied menu of meals that allow the riders to maintain their performance over three weeks, promotes recovery from the rigours of the day, and helps to maintain health and wellbeing.

On a typical day a Tour rider will eat 3,500 to 4,500 calories. On particularly hard stages this may be as high as 9,000 calories. They start with breakfast usually a few hours before the race. Then there are energy drinks and bars on the team bus on the way to the start line. During the race they’ll munch on a mixture of solid food, gels, and drinks carried in their pockets or on the bike. At the feed-stations they’ll grab a musette which will contain sandwiches and possibly cake as a welcome alternative to the bars and gels. Typically riders will eat two to three items of food (including energy drinks) and drink 500 millilitres of water per hour. Post-race they sup on recovery drinks and eat sufficient protein to kickstart the recovery process. Then there’s the evening meal where the bulk of the days calories are consumed. Salads, meat, vegetables and carbohydrates are the order of the day, Finally the riders might snack on milk and cereal, a protein shake, or yoghurt and honey before bed.

It’s a far cry from Robert Jacquinot sat on his own in a café at Hostens, legs crossed, supping soup from his spoon as the mud dries on his legs. He abandoned the race two days later somewhere between Bayonne and Luchon on a stage that included the climbs of the Col d’Aubisque, the Col d’Aspin, and the Col de Peyresourde. One imagines that the mountains proved too much for him. Perhaps he’d also not eaten enough.

The Italian cyclist Felice Gimondi eating his daily food ration during the Giro d’Italia. Sanremo, 24th May 1968 (Photo by Giorgio Lotti/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images)

I love all of these images. I have a framed Tour poster of Swiss racers Colle and parcel taking a break, drinking a huge glass of beer in Moselle (1921).

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s a classic photo which may just be making an appearance on these pages in the not too distant future

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on PedalWORKS.

LikeLike

I really enjoy your posts. I have just reblogged your latest.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s been fun researching and writing this series. Glad you’re enjoying it.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Kite*Surf*Bike*Rambling and commented:

An amazing blog post about how the riders and racers in the past used to pace themselves

LikeLiked by 1 person