Military Cycling: The British Army Chooses a Bicycle

Following the successful manoeuvres of 1887, and the less successful manoeuvres of 1888, the British Army continued to examine the utility of the bicycle for military purposes, and in June 1888, Lieutenant-Colonel A. R. Savile presented a paper to the Royal United Service Institution. Having established that “the power to transport infantry rapidly from point to point in a theatre of war” was “one of the most urgent requirements of modern warfare”, Savile briefly outlined developments in the use of the bicycle for military purposes on the continent and in Britain, proceeding to discuss what type of bicycle was most suited to military use, and how cyclist infantry might best be utilised and deployed.[1]

As the Commanding Officer of the Volunteer cyclists during the 1887 and 1888 Manoeuvres, and the president of the War Office Committee appointed to report on the training, equipment, clothing, and bicycles best suited for military purposes, Savile was without doubt the subject matter expert in the British Army in 1888, and well qualified to comment. When it came to the type of machine needed, Savile identified five types to choose from:

(1.) The ordinary bicycle.

(2.) The rear-driving safety bicycle.

(3.) The single tricycle.

(4.) The tandem tricycle, carrying two riders.

(5.) Multicycles, carrying more than two riders.[2]

The ordinary, or penny-farthing, was dismissed out of hand as unsuitable for military use due to its high centre of gravity and the greater risk of accident, its greater visibility resulting from its height, and its practical limitations for carrying arms, ammunition and kit. The tricycle, though extremely stable, was unsuited to rough roads and could not traverse open country without great difficulty. Multicycles, it was noted, were in their infancy, and though they might be adapted to transport machine guns, materiel, equipment, and ammunition, the trial of two models at the 1888 Easter Manoeuvres had seen them quickly put of service by mechanical failure, with the 26th Middlesex’ three-man cycle hauling a Maxim gun having to be abandoned altogether.[3]

One reason why the penny-farthing was unsuitable for military purposes (Source: The Graphic, March 31, 1888)

The most suitable bicycle by far, according to Savile, was the rear-driving safety. It was as fast as an ordinary, was “practically safe down any hill”, and could carry all a soldier’s equipment. Compared to an ordinary it was easier to mount and dismount, had better handling, and was easier to transport.[4]

Having established that the safety bicycle was the type most suited for military use, Savile outlined the relative merits of the bicycle: Unlike the horse it required no forage or water, and could be left unattended when the men were in action. Cyclists were less visible and audible than cavalry. It required far less maintenance and support than horses. If provided to the Army as a standard model its components would be interchangeable, allowing for cannibalisation of parts for repairs. And it was easy to transport, it being a quick process to pack bicycles into “any kind of van, truck, or carriage, without the aid of a platform”. Finally, compared to the horse, the bicycle was relatively inexpensive, with Savile estimating that an efficient safety bicycle for military use could be obtained for £12 per unit given economies of scale in purchasing.[5]

Savile’s paper was a timely summary of progress thus far. By June 1888 several Volunteer cyclist corps had been established, with the first formed being the 26th Middlesex (Cyclist) Corps which were to be commanded by Captain Percy Hughes Hewitt of the Reserve of Officers, who was to be promoted to Major from April 1st 1888.[6] They were joined at the 1888 Easter Manoeuvres by the cyclists of the Bristol Engineer Corps, and those of the 28th Middlesex.

The regular Army had also begun to assess the utility of the bicycle at Aldershot with a scheme of training under the supervision of Major G. M. Fox, the Assistant Inspector of Gymnasia. Bicycles of various types had been purchased from Singer & Company, Coventry, and were being tested.[7] Despite the interest, and the growing number of Volunteer Cyclist Corps, progress in adopting the bicycle for the regular Army was relatively slow.

In March, 1899, Captain Baden Fletcher Smyth Baden-Powell, the younger brother of Robert Baden-Powell founder of the Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, presented another paper on the theme of military cycling to the Royal United Service Institution, titled, “The Bicycle for War Purposes” [8]. With plans in place to implement a regular programme of training at Aldershot, Baden-Powell argued that it was now time to “decide on the exact pattern of machine most suitable for military purposes.”[9] Whilst Savile had restricted his discussion to the relative merits of the bicycles available in 1888, Baden-Powell additionally examined the circumstances under which they might be put to use, and the way in which military bicycles might be employed in his discussion on the machines the Army would need.

Three situations where bicycles might be used were identified:

1. At home, in case of invasion.

2. Abroad, where the roads are good and plentiful.

3. Abroad, where the roads are comparatively few and bad.[10]

Each scenario favoured a different type of machine. A light bicycle would facilitate rapid movement in home territory where roads were plentiful and good and the logistical problems of supply, repair and maintenance were of low magnitude. A more strongly built bicycle capable of load carrying was recommended when abroad in areas that had a good network of maintained roads. And in countries where the roads were poor the bicycle would need to be robustly built.[11]

Having established that different circumstances ideally required different equipment, Baden-Powell proceeded to enumerate on the ways in which bicycles might be employed.

1. Strategical – Specifically the strategic movement of large bodies of troops to the departure or concentration points independently of railways.

2. Raiding – Rapid marches into enemy held territory to achieve a specific object such as the destruction of a bridge, cutting communications, or the relief of another force.

3. Scouting and Reconnaissance – From the base of operations, or acting as rear or advance guards.

4. As Mounted Infantry – Operating as part of a force of all arms as escorts or convoys to cavalry, guns, or rapidly moving supply columns, and fighting as infantry if engaging the enemy.

5. As Orderlies and Messengers

6. For Transport – Providing an emergency transport role in rapidly bringing up ammunition and materiel to the line, bringing up supplies from the rear, supporting a flying column, and acting as stretcher-bearers in extremis.

7. Special Purposes – Including signals, telegraphy, and topography, where the bicycle could not only provide a means of transport allowing the soldier to stop to carry out their function and then quickly catch up with a column, but could be utilised as a cyclometer, clinometer, or plane-table [12]

If the various ways in which military cyclists might be put to use ideally required the Army to make use of different types of bicycle, financial expediency, as well as practicality, required an all rounder that could be put to multiple tasks. To survive the rigours of the field an Army bicycle would need to be strong, simple to maintain and repair, and have a minimum of accessories in order to reduce the potential for any mechanical failure. A standard model would allow for interchangeable parts, facilitating repair in the field. Wheels of the same size would allow for tyres to be interchangeable, additionally reducing the requirement for logistic support. And, given the weight of a bicycle ridden by a soldier carrying full kit and perhaps additional materiel, the brakes would need to be simple and strong [13]. Cyclists of any generation, before or since, would no doubt empathise with Baden-Powell’s observation that:

I never could find any two people agree as to the best form of saddle. I believe all kinds can be got accustomed to after a few rides. but that we are all equally uncomfortable after three or four hours’ steady riding [14].

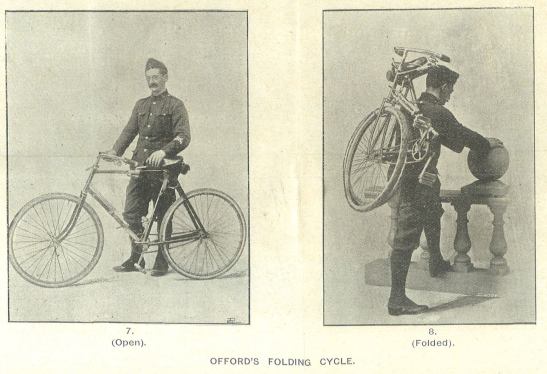

Curiously, Baden-Powell stopped short at recommending a specific type of bicycle, instead discussing the relative merits of folding bicycles in terms of being easier to carry and their compactness in storage and transport. These benefits were largely outweighed by their weight and the greater potential for mechanical failure resulting from a more complicated construction [15].

It’s possible that Baden-Powell’s seeming reticence in advocating a specific type of bicycle may lie in his brief discussion of a machine of his own design, the “Tripartite”, a modified safety bicycle that allowed for the forks, front wheel, steering post, and handlebar to be detached from the head of the frame. According to Baden-Powell the process was quicker than that for a folding bicycle, produced a flatter profile for stowage, and had the advantage that the frame remained intact, making it more durable [16].

Two years later, the Army introduced its first officially adopted bicycle in the List of Changes, known as “Bicycle (Mark I) High, Medium, Low”, referring to each model’s suitability for riders of differing stature, with the description:

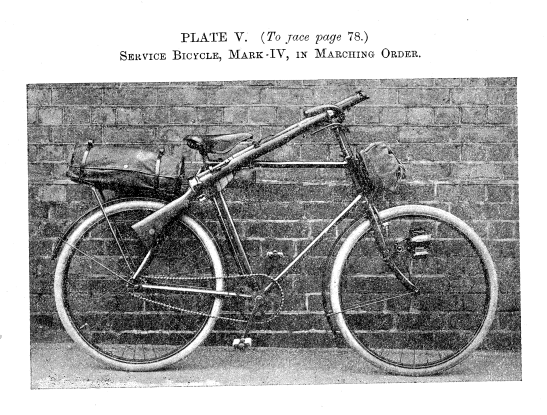

General Service, with bell, lamp, pump and pump clips (2), cycle rest complete with brake strap and back stay clip, fornt and rear carrier with 1 loose and 2 fixed straps on each, saddle, rifle clips (2), and tool bag containing oil can, outfit, spanners (3), and bottle, oil, M.L.M. (Mark III)” [17]

Once officially adopted by the British Army, development was relatively rapid. The Mark II was introduced in 1902 with a free-wheel hub, a shorter wheel base, and alterations to several components, The Mark III followed in 1908, introducing a coaster hub with free wheel clutch, and alterations to the frame, front forks, and other parts. As per the recommendations of Savile and Baden-Powell, the standard models allowed for interchangeable parts between bicycles of the same model, and between Mark I and Mark II, and Mark II and Mark III bicycles. In 1911 the Mark IV was approved. Unlike previous Mark’s it was only available in one frame size of 24 inches and had upturned, instead of flat, handlebars [18]. The standard pattern laid down in the List of Changes meant that any manufacturer could supply bicycles to meet the Army’s requirements, and though BSA were a preferred supplier from 1901, companies such as Raleigh, Columbia, Rudge-Whitworth, Sunbeam, and Royal Enfield also produced military models.

Savile and Baden-Powell’s recommendations for a robust bicycle of simple construction and standardised form, that was capable of load carrying, was realised in the Mark I to IV Service Bicycles. The Mark IV, and its variant the Mark IV*, were to be the most common bicycle in use among the British Army throughout the next decade, seeing service throughout the Empire and in all theatres during the First World War. Less prophetic though, were their, and other officers, thoughts on the fighting capabilities of the military cyclist as the new realities of war in the early twentieth century were to subsequently demonstrate.

______

Endnotes:

[1] Lt-Colonel A. R. Savile “Military Cycling”, Journal of the Royal United Service Institution 32, no. 145 (June 1888): 731-755.

[2] Ibid., 740.

[3] Ibid., 740-741; “The Easter Volunteer Manoeuvres: With the Cyclist Corps”, The Graphic, April 7, 1888, 371.

[4] Savile, “Military Cycling”, 740.

[5] Ibid., 743-744.

[6] The London Gazette, no. 25790, February 24, 1888, 1228; “Volunteer News: A New Cyclist Corps”, Gloucester Citizen, February 18, 1888, 3.

[7] Savile, “Military Cycling”, 736.

[8] Captain B. F. S. Baden-Powell, “The Bicycle for War Purposes”, Journal of the Royal United Service Institution 43, no. 257 (July 1899): 714-736.

[9] Ibid., 716.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid., 716-720.

[13] Ibid., 721-726.

[14] Ibid., 726.

[15] Ibid., 722-723.

[16] Ibid., 723-724.

[17] List of Changes in British War Materiel, 1901, § 10802.

[18] Ian Skennerton, “Pedal Power … The British Military Bicycle”, Arms & Militaria Collector 5, no. 2 (1991): 31-36.

Fascinating!

LikeLike

I found your site thru googling for Lieut-Colonel Savile. He was deeply involved with the women’s suffrage movement in Hastings, serving as treasurer of a society, chairing meetings etc. One anti suffragist referred to Savile as “the wag in the corner” at meetings, which reveals something of his personality.

LikeLike

My brief biog notes on him. Lieutenant-Colonel Albany Robert Savile 1844-1917 was honorary treasurer of the Hastings Women’s Suffrage Propaganda League. He was a member of the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage. He lived at 9 Holmesdale Gardens, a 14-roomed villa. Born in Edinburgh. In 1869 he married Sybella Twemlow. She died 1929, Hollingdene, St Leonards. Retired commander of the Royal Irish Regiment, he was a keen cyclist and his regiment were on bicycles. They were featured in an illustrated article in the Strand Magazine. He was at some point based at the Royal Military College, Sandhurst.

LikeLike